Modernizing Medicine Associates Explain How to Combat Health Inequities

On August 19, three Modernizing Medicine associates spoke to Texas Ambulatory Surgery Center Society members about implicit bias in the healthcare system and how healthcare providers can work to narrow these inequities.

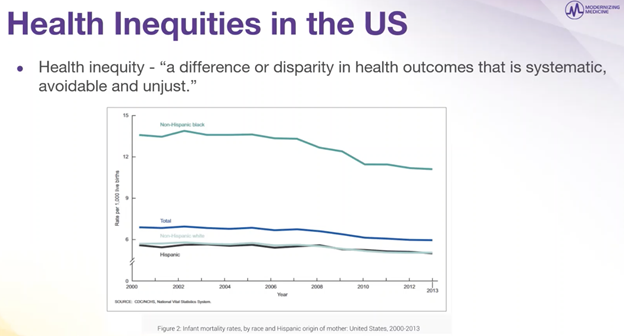

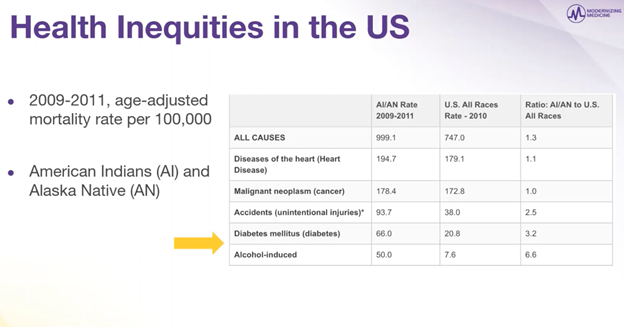

Julie Servoss, senior medical director of gastroenterology, Tacoma Perry, a medical consultant, and Michael Rivers, director of ophthalmology, began the conversation by contextualizing health inequities in the United States. Servoss talked about several areas of noticeable discrimination, including infant mortality rate and age-adjusted mortality rate.

The infant mortality rate is a health metric used by the World Health Organization as a metric for healthcare systems across the globe, Servoss said. In the United States, this graph from 2000 to 2013 charts infant deaths from zero to one, and a disparity becomes apparent when comparing white baby deaths to that of black baby deaths. While this is only over the span of the 2000s, Servoss added that this data is similar across several decades.

When continuing to stages of adult life, Servoss pointed out the inequalities between American Indians and Alaska Natives were significant when looking at mortality rates by accidents, diabetes and alcohol. The data further shows how intensely these inequities exist for minorities in the United States.

The notion of race has been baked into the way that US clinicians are supposed to handle medicine, from diagnosis to treatment plans. Racial discrimination even seeps into medical algorithms used for risk assessment and healthcare systems. “We are socialized to think in terms of race,” Servoss said.

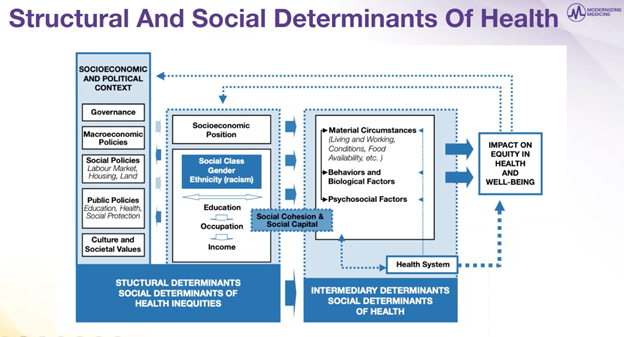

The truth is that about 30% of health outcomes are determined by genetics, but socioeconomic and structural factors determine the rest. “These are the types of factors that are so important and, even better, are adjustable,” Servoss said. “We can narrow these inequities.”

A prime example of how significantly these factors can affect health comes from life expectancy in different parts of New Orleans. Neighborhoods in different areas of the city vary in life expectancy by as much as 25 years — something that cannot be explained by genetics.

The cultural and social determinants of health Servoss went over were revealing in more ways than one. “This is showing both the problems, but also it helps to find some of the solutions,” Rivers added.

The chart communicates how caregivers could potentially structure their practices to help combat some of the negative factors in these determinants. “These are challenges that black people have had in society since I went to medical school in the late ‘80s,” Rivers said. “None of this is new, but the solutions are in this slide — things we really have control over.”

Beyond the medical practices, Perry expressed how caregivers should integrate into the communities they serve. “It’s important to have that trust with your healthcare provider because it trickles down for generations to come.” Servoss added that grassroots intervention in the community helps caregivers adapt to the challenges and opportunities of the specific area.

By continuing to educate medical personnel and working to combat the socioeconomic structures that have been ingrained in society for so long, caregivers can continue the efforts to reduce health inequities and create a more beneficial practice for all their patients.